Given the start of 2022 budget deliberations at the City of Seattle, this blog post updates our original

Follow the Money post from 2020, showing how the Seattle Police Department (SPD) budget remains outsized compared to spending on other critical city departments. In 2021, Mayor Durkan and the City Council made rather modest cuts to the

Seattle Police Department’s (SPD) 2021 Adopted Budget. Many of the cuts resulted from transferring functions to other departments, which means the money was not freed up for other uses. 911 dispatch was moved from SPD to the newly minted Community Safety and Communications Center (CSCC), the Parking Enforcement Unit was moved to the Seattle Department Transportation (SDOT),

[i] and the Office of Emergency Management (OEM) was moved to its own standalone department.

Although these efforts to civilianize public safety and shrink the role of the police in our communities are a step in the right direction, it is not the same as what community has been calling for —

police divestment and community reinvestment. The divest-reinvest approach means diverting funds towards community-based and community-led approaches to public safety, which would, for example, create more affordable housing, invest in better and more affordable healthcare, improve access to mental health care, and create jobs programs – as opposed to simply moving police budget line items to other city departments but essentially leaving things unchanged. The diversion of these funds shows real evidence of improved public safety as we outlined in a

recent blog post.

2022 budget negotiations began on September 27, 2021, and will conclude on November 22, 2021, when the City Council adopts the new budget. The information below serves to keep you informed about how the City of Seattle is funding policing, as well as other critical services.

Review of 2021 policing budget

Cuts Made to the 2021 Budget are Modest – Mostly Transfers of Police Functions to Other City Departments

The 2021 adopted SPD budget is nearly $363 million. During the previous budget cycle, the Mayor and City Council made about $70 million in cuts, but because of funds added elsewhere in the police budget, the net reduction was $46.1 million (about 11 percent) from the 2020 Adopted Budget of $409.1 million.

Mayor Durkan’s proposed cuts included:

- moving some functions such as parking enforcement and 911 dispatch, both of which are carried out by civilians as opposed to sworn officers,[ii] out of SPD into other city departments ($38.3 million)

- eliminating sworn officer positions that were vacant as a result of attrition, reducing overtime due to the COVID-19 pandemic cutting down on the number of events, and savings from a civilian hiring freeze ($22.4 million)

The City Council’s budget package included an additional $12 million in cuts by:

- eliminating a few dozen more officer positions that were unlikely to be filled ($8.1 million)

- transferring the funding for contracted mental health providers (MHPs) serving the SPD Crisis Response Unit (CRU) from SPD to the Human Services Department ($450,000)

- This is a small line item relatively speaking but this move reduces reliance on police to deliver crisis response and redirects resources to non-police response, consistent with the divest-reinvest approach.

- reducing overtime ($3.7 million).

The SPD Budget Remains Outsized According to Several Measures

1. Police budget as a proportion of the General Fund

Funding for police comes largely from the City’s General Fund, which is taxpayer generated

[iii] and is the City’s primary operating budget for all the services it provides. It is a discretionary fund, which means the City Council has flexibility with regard to how it spends those funds (in contrast to “restricted” funds, which must be spent on specific services). The SPD 2021 Adopted Budget constitutes a whopping 22.5% of the $1.6 billion General Fund, which 42 other city departments

[iv] rely on (at least in part) to fund their operating expenses. Other departmental funding streams may include, among other things, grants and levies, and are generally reflected in the budgets discussed below.

[v]

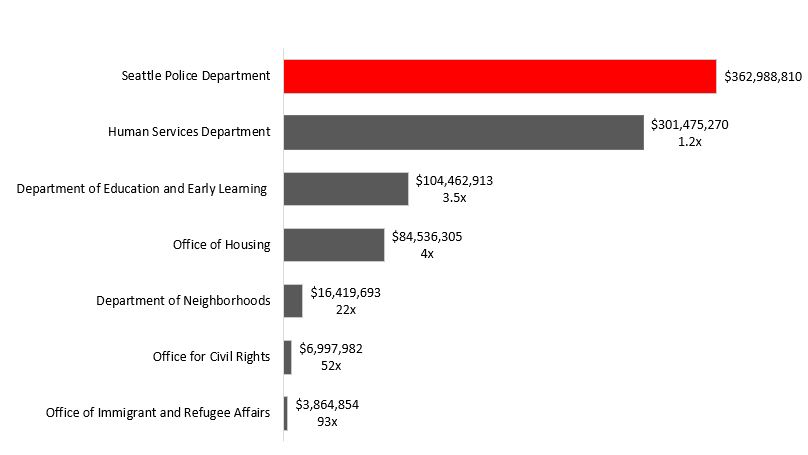

2. Police budget compared to other select City departments

Another way to think about how outsized the SPD budget is to consider how large it is compared to other city departments that provide services to our communities, such as education and housing. Comparisons help put the police budget in context.

Figure 1: SPD Budget Relative to Other Select City of Seattle Departments, 2021

Source: Seattle City Budget Office, “2021 Adopted Budget”

Compared to other City of Seattle departments, the SPD budget is (Figure 1):

- 93 times bigger than the Office of Immigrant and Refugee Affairs

- 52 times bigger than the Office for Civil Rights

- 22 times bigger than the Department of Neighborhoods

- 4 times bigger than the Office of Housing

- 3.5 times bigger than the Department of Education and Early Learning

- 1.2 times bigger than the Human Services Department

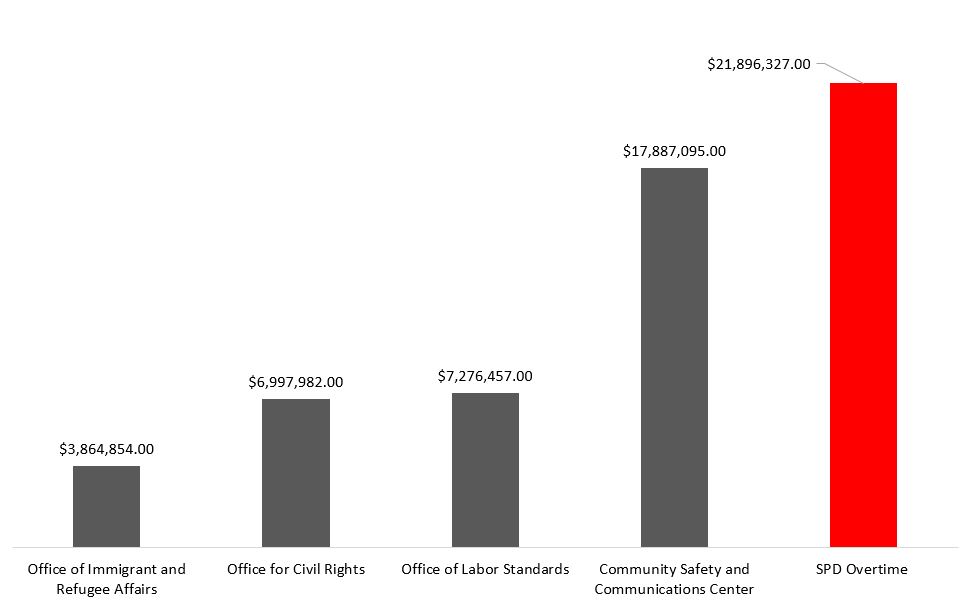

3. Police overtime budget compared to select City departments

Finally, the SPD’s 2021 budget remains outsized when you consider how much the department is allocated for overtime alone (Figure 4). In 2021, SPD’s overtime budget shrank by 27% — from about $30 million in 2020 to about $22 million in 2021. It constitutes 6% of SPD’s total 2021 budget; last year, it was 7% of the total 2020 budget. This (temporary — see below) cut was due to a reduced need for police to staff sports events and other community events, many of which were canceled as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, the overtime budget remains larger than the budgets of more than half (23) of the other City departments funded by the General Fund, including the CSCC, which was created as part of an effort to

“shift away from a police-centric approach to public safety” (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: 2021 Seattle Police Department Budget Compared to Select City Department Budgets

Source: Seattle City Budget Office, “2021 Adopted Budget”

Why do we care about the size of the police overtime budget? Overtime is an important labor tool for compensating workers for the extra time they have worked. However, in the context of policing, its misuse is a systemic problem. A

blog post we wrote last year does a deep dive on the nature of this misuse and in particular the role of the officers’ union, the Seattle Police Officer Guild (SPOG). Ultimately, the overtime budget alone is substantially larger than most other Seattle departments, and it has become a backdoor way of growing SPD’s budget, with little oversight as to how this money is spent.

The issue of overtime is emblematic of the fact that the Adopted Budget for SPD does not reflect all the money that is dedicated to policing on a yearly basis. For example, the budget does not account for

pension and medical benefit services for retired police officers which they are

often entitled to collect even if they are fired for misconduct (even criminal misconduct) and are paid for out of the General Fund. Money for settlements also comes from the General Fund, including all the costs associated with implementing the

Consent Decree, the settlement between the federal Department of Justice and the City of Seattle, which has so far cost the city over $100M.

[vi] Although in theory settlements help with accountability, a divest-reinvest approach (which relies on creating public safety primarily through upstream investments in community rather than in police) reduces opportunities for police abuse from happening in the first place, which eliminates all costs associated with these settlements.

The 2022 Proposed SPD Budget: What’s at Stake

Despite the transfer of several functions (and those large budget lines) out of SPD, the

Mayor’s proposed 2022 budget for SPD remains relatively the same — $365.4 million, compared to nearly $363 million in 2021. This is largely due to budget adjustments for one-time technical changes (increases) to the 2021 Adopted Budget.

Most of the substantive changes to the budget involve moving around money that is technically already in the SPD budget--what SPD refers to as “salary savings.” These dollars result from the SPD’s inability to fill funded positions (i.e. positions that the department has authority and funding to fill but that they acknowledge they will not be able to hire for). The SPD has seen unprecedented sworn officer attrition in the last couple of years, but instead of leveraging the funding associated with those departures to ramp up police alternatives, the Mayor’s proposed budget lets them keep it.

In fact, the Mayor’s proposed budget would increase the sworn salary funding from 1,343 in 2021 to 1,357 in 2022.

However, current SPD staffing projections show that the department is only trying to fill 1,223 FTEs in 2021 (due to further projected attritions). In other words, although the SPD would receive funding for 1,357 sworn positions, SPD only plans to employ 1,223. Even reaching this lower number requires meeting an

ambitious hiring goal; it assumes SPD will hire 85 sworn officers this year (they have only hired 53) and it assumes they will hire 125 next year, even though they have never hired more than 108 in a given year. The difference between the funding needed to support 1,223 sworn positions (what SPD claims they will hire) and the funding needed to support 1,357 sworn positions in the 2022 Proposed Budget, which SPD has made clear it will be unable to reach, is $19.4 million. This is money that

SPD is asking to keep to spend on other items--in effect, a department slush fund. Community groups like

Decriminalize Seattle argue that these unfilled positions should be eliminated, freeing the money for community-based, non-police responses. This move is supported by

third party analysis from the National Institute for Criminal Justice Reform (NICJR), commissioned by Mayor Jenny Durkan, which found that

up to 49% of 911 calls do not require response by an armed officer and could be handled via an “alternative , non-sworn response.”

Conversely, SPD is proposing to spend it on, among other things,

hiring incentives (bonuses), technology investments, a new team of Community Service Officers, and “restoring” the overtime budget to its 2020 amount.

No other city department is allowed to put together a budget proposal like SPD’s. For other departments, positions that are not planned to be filled are eliminated and the funds go back to the City’s General Fund; the department does not get to keep the funding to spend elsewhere.

Take Action Now to Influence the 2022 Police Budget

The Mayor has submitted her proposed budget, and on October 27, the Seattle City Council presented

a series of amendments to her budget proposal for SPD, including:

- Proviso (restrict) funding for new technology investments ($2.5 million of the $5 million in the proposed budget) until SPD can provide more details about the costs and benefits of the projects and a plan for each of the technology projects. The City Council also requested SPD focus initial tech spending “in a manner that prioritizes Consent Decree reporting, officer wellness, and evaluation of the NIJCR study on Seattle Calls for Service Analysis.”

- Proviso funding for CSO officers ($200,000) and on sworn salary savings ($5 million), with the intent of using some of it for other Council budget priorities if the conditions for lifting the proviso are not met.

- Cut sworn salary savings and efficiency savings (e.g. reduction in number of officers deployed on overtime to events or demonstrations) and redirect it to other Council budget priorities ($4.5 million)

- Cut hiring incentives for new officers ($1.1 million) and add it to the Finance General budget to implement a Citywide hiring incentive program. This was proposed in light of the existence of citywide vacancies, including at the emergent CSCC, which is “struggling to fill vacant call-taker and supervisor positions.”

There were also two walk-on amendments (i.e. last minute amendments for which a Statement of Legislative Intent, explaining the action in detail, had not yet been written):

The Seattle City Council will continue to shape their 2022 budget package in the coming weeks:

- November 10: PUBLIC HEARING at 5:30 pm

- November 12: City Council presents its Balancing Package

- November 18: PUBLIC HEARING at 11 am

- November 18-19: Amendments to the Balancing Package

- November 22: City Council adopts the 2022 budget

This is your chance to weigh in on what the SPD budget will look like. SPD is heavily prioritized over city departments dedicated to education (350% more), housing (400% more), and human services (20% more) which supports services for those facing poverty.

What does that say about Seattle’s values? Do you agree with the way your City Council members and Mayor have prioritized spending on policing versus critical city services like housing and human services, despite the fact that

data shows those services are crucial to reducing crime and violence? If not, please turn out for the

two remaining budget public hearings on November 10 and November 18, and make your voice heard!

[ii] Sworn officers (e.g. police officers) carry a firearm, have the power to make arrests, and carry a badge. They also go through training at the academy. Civilian officers (e.g. 911 dispatch, parking enforcement) do not have these features.

[iii] 84.5 percent of the 2021 General Fund is generated by taxes including property, sales, payroll, business and occupation, and utility taxes.

[v] “For many departments…several funds, including the General Fund, provide the resources and account for the expenditures of the department. For several other departments, the General Fund is the sole source of available resources.” City Budget Office, “City of Seattle, Washington 2021 Proposed Budget,” available at http://www.seattle.gov/Documents/Departments/FinanceDepartment/21proposedbudget/2021%20Proposed%20Budget.pdf.